march 2021

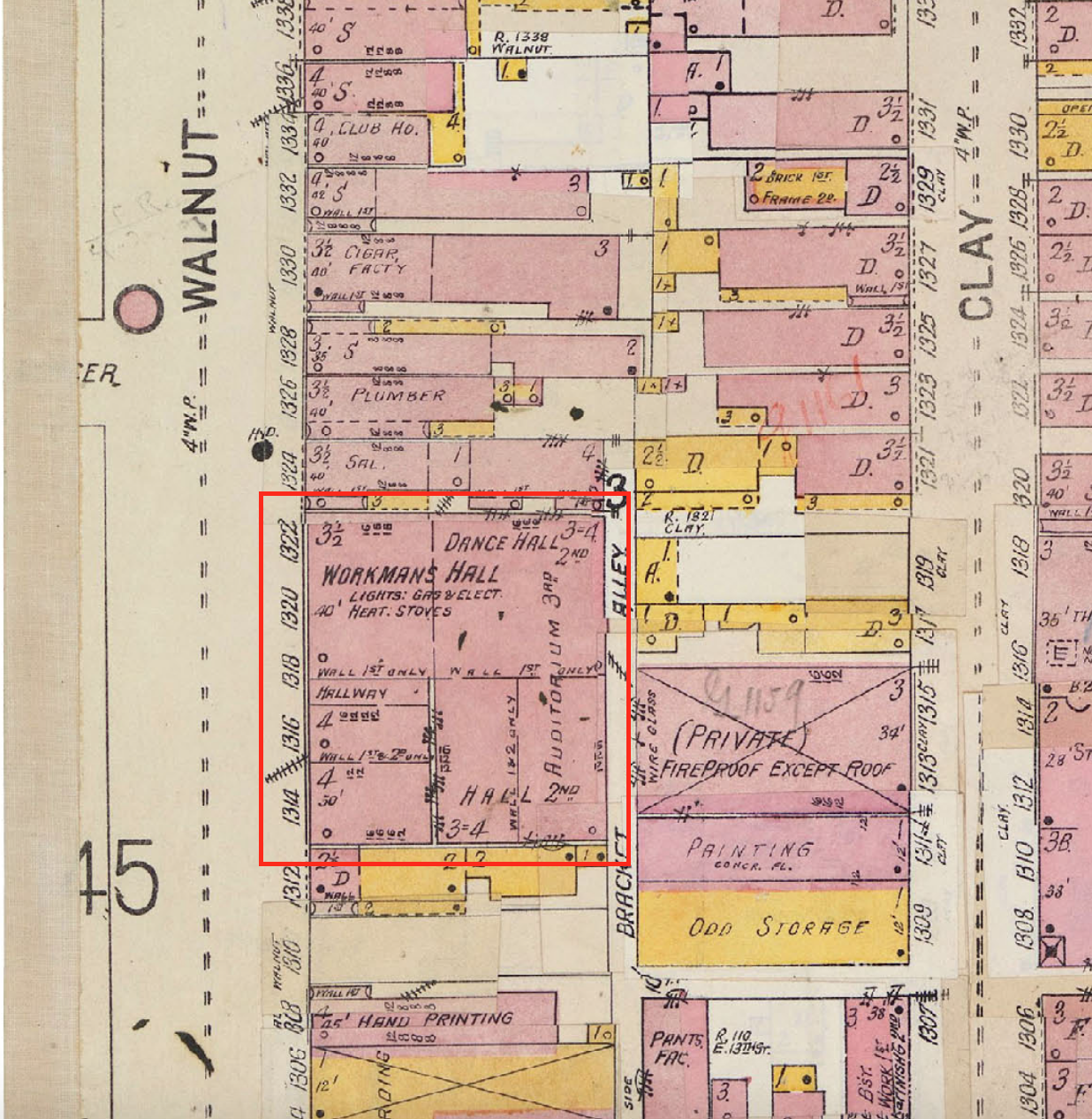

Workman’s Hall, also known as Workingmen’s Hall, Arbeiter Hall, and “The Labor Temple”, was a gathering hall and union room for workers. It was built by German workers in 1859 and was located at 1314 Walnut St. in the Over the Rhine neighborhood of Cincinnati, OH. It became a hub for union and socialist organizing in Cincinnati, and acted as the headquarters for dozens of labor organizations, including the Trades and Labor Assembly, Workingmen’s Party, the Knights of Labor, the Central Labor Council (a local affiliate of the American Federation of Labor), and many local industrial and trade unions. The Cincinnati chapter of the Populist Party, a national party which was founded in Cincinnati in 1891, also met at Workman’s Hall. The Hall was utilized by a diverse range of workers— men and women, adults and children, immigrants and native-born people. Hundreds of strikes were organized at and staged out of Workman’s Hall over the course of its existence. In 1920, it was the largest establishment of its kind in the United States. The building included a dance hall, several auditoriums, a union co-op store, a bath house, and an outdoor biergarten. The original building has since been demolished.

At the end of the American Civil War, conditions were ripe for labor organizing in Northern cities. In many cases, working men’s experiences fighting in ethnically-diverse battalions during the Civil War had the effect of lessening ethnic tensions, creating favorable conditions for working class solidarity. At the same time, craft unions and artisan guilds were beginning to decline, giving way to modern-day trade unions. A further development in labor organizing was the rise of industrial unions and nation-wide unions, which did not organize workers by trade or by shop, but rather industry-wide, maximizing the amount of power workers could wield in collective bargaining efforts against employers.

By the end of 1865, there were at least 40 active labor unions in Cincinnati, and between the years of 1864 and 1867, there were 36 strikes staged within various industries across the city. Individual labor unions that did not have buildings of their own, such as the Brewer’s Union, the Carpenter’s Union, and the union of Carriage and Wagon Workers, used Workman’s Hall as their meeting space, often meeting on a weekly basis. In addition, the Central Labor Council, a local affiliate of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), was headquartered at Workman’s Hall. The Central Labor Council acted as a “union of unions”— each union that joined maintained its own autonomy, but worked alongside, and received support from, the other member unions to improve the conditions of the working class as a whole.

Another prominent organization that was headquartered at Workman’s Hall was the Trades and Labor Association (TLA), which had become a major force by the spring of 1864. The TLA’s vision was to unify all workers as a class, and to this end, they created the Workingmen’s Party— a political party by and for the working class. They were successful in uniting German, Irish, and native-born white and black people, women and men, journeymen and laborers, into their organization. When an anti-strike bill was passed in the Ohio State Legislature in March of 1865, the TLA successfully defeated the bill through their organizational efforts.

The TLA’s major project was to institute the eight hour work day at a time when working 12-hour shifts, without breaks, was not uncommon. The Workingmen’s Party elected Samuel Fenton Cary of the College Hill neighborhood to U.S. Congress in 1867, where he championed the first-ever bill for an eight-hour working day. According to the Cincinnati Bookbinder’s Union, the bill was drafted in Workman’s Hall itself. The bill was initially passed and later overturned, and the eight-hour working day has had to be continually fought for and defended by working people ever since.

Workman’s Hall continued to play an important role in the fight for an eight-hour working day long after the TLA’s initial efforts. A Cincinnati Enquirer’s article about a May Day celebration held at the hall in 1895 says that “the object of the affair was not merely for the purpose of inauguration May Day exercises, but also for the purpose of having addresses made with a view to impressing more forcibly the necessity for keeping up the eight-hour laboring day” (“Labor: Organizations Hold May-Day...”).

The TLA was successful in accomplishing a few of its goals through the Workingmen’s Party over the course of its lifespan. However, the establishment Republican and Democratic parties soon realized the threat a third party posed to them. They promptly set up shop in Workman’s Hall and systemically recruited Workingmen’s Party leaders into their ranks, leading to the party’s decline.

According to the Cincinnati Bookbinder’s Union, local labor organizations used Workman’s Hall as the campaign headquarters to push for nearly 40 amendments to the Ohio Constitution which were signed into law in September of 1912, including the initiative and referendum reforms. Agitations for free text books for school children and anti-child labor laws originated at Workman’s Hall. The Hall also hosted national conventions for various international unions.

The building in which Workingman’s Hall was located was built by the Arbeiter (“Worker” in German) Stock Company. It was leased to the Boot and Shoe Workers with privilege of purchase several years after it was built. The Boot and Shoe Workers raised over $85,000 to have the building remodeled and refitted, and then sold small stock shares of the building to local trade unionists, making sure “to keep the building in the hands of the unions” (The International Bookbinder.)

The following is a description of Workman’s Hall written in 1920 by the Cincinnati Bookbinder’s Union:

“[The Labor Temple] is the largest establishment of its kind in the United States. In addition to five large auditoriums, there are several small lodge rooms, committee rooms, and offices for business agents. On the ground floor is a club room, one of the few in the world for organized workers. Here they have pool and billiard tables, a dance hall, card and checked tables, book shelves and racks for periodicals, shower baths and on the same floor a union co-operative store, where strictly label goods, soft drinks and cigars are sold… Now it is at last coming into its own, and Cincinnati will have a real Labor Temple— a real home for the workers— a place of welcome for the thousands of union men and women who will be coming to Cincy to attend the next world’s series— of 1920.”

Workman’s Hall acted as headquarters for some of the most radical labor organizing to be carried out in Cincinnati during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with many prominent leaders self-identifying as socialists and communists. The following quotation from an 1894 speech given at Workman’s Hall, as reported by the Cincinnati Enquirer, exemplifies these sentiments:

“It has been said that wage work represented the last and highest stage of civilization. I do not think so. All signs point to the final organization for the interests of labor. Then there will be centers of industry where workingmen will employ themselves for their own sakes. Before that time comes to pass organized labor and organized capital will meet face to face” ("Plain Talk...").

In 1896, the CLC organized several speeches by prominent socialist labor leader Eugene V. Debs at Workman’s Hall and other public arenas in Cincinnati. The crowd drawn together by Debs was described by the Cincinnati Enquirer as a “monster gathering… One of the largest audiences that ever assembled” in the halls in which he spoke ("Debs: The Great Labor Leader..."). At his speech at Cincinnati’s Robinson’s Opera House, Debs was greeted by a five-minute standing ovation, and he proceeded to give a two-hour speech, uninterrupted except by frequent applause. The following is an excerpt from the Cincinnati Enquirer:

“[Debs] said the great problem of today was the existing differences between centralized capital on the one side and organized labor on the other. Continuing, Mr. Debs said ‘The centralizing of wealth and the amassing of great fortunes in the country at the present time stands without parallel in the world’s history and has created a power which dominates every part of our Government.’ Mr. Debs dwelt at great length upon the effect of money in every walk of life, and even went so far as to say that it could accomplish anything” ("Debs: The Great Labor Leader...").

The night following this speech, Debs spoke at Workman’s Hall to yet another enthusiastic crowd.

In addition to being a meeting space for unions and labor organizations, Workman’s Hall was used as a social event space. A Cincinnati Enquirer article from 1895 describes a masquerade ball held by the Superior Fishing and Outing Club which was attended by over 2,000 people. May Day events were held yearly on May 1st at Workman’s Hall, complete with speeches and musical and dance performances, as well as group singing and dancing. Theater performances were also hosted in the hall, such as the “Hobo Show” of 1912, which provided social commentary on the effects of automation on the working class ("Hobo Show..."). Members of the unions that owned stock in the building were able to utilize it for private parties and wedding receptions.

Given its location in Over the Rhine, which was a German immigrant-majority neighborhood at the time, many of the events held at Workman’s Hall were bilingual, addressing the crowd in both English and German.

“Arbeiter Hall Partially Destroyed by Fire.” The Cincinnati Daily Enquirer (1852-1872); Apr 30, 1867; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Cincinnati Enquirer pg. 2

“At Workman's Hall.” Cincinnati Enquirer (1872-1922); Feb 27, 1895; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Cincinnati Enquirer pg. 8

Blackpast. "(1877) Peter H. Clark, 'Socialism: The Remedy for the Evils of Society.'" Blackpast.org; January 28, 2007. Accessed 29 March, 2021.

“DEBS,: THE GREAT LABOR LEADER, ADDRESSES A MONSTER GATHERING” Cincinnati Enquirer (1872-1922); May 9, 1896; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Cincinnati Enquirer pg 8.

“DEBS: ON THE LECTURE STAGE. ACTIVITY IN ALL LINES OF TRADES UNION …” Cincinnati Enquirer (1872-1922); May 10, 1896; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Cincinnati Enquirer pg. 18

“ENTHUSIASTIC: MEETING OF MESSENGERS. STRIKERS GATHER IN GOODLY NUMBERS. THE BOYS GIVEN SOME ADVICE BY LABOR LEADERS.” Cincinnati Enquirer (1872-1922); Jul 24, 1899; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Cincinnati Enquirer

"HOBO SHOW: PLEASED AUDIENCE AT WORKMAN’S HALL— THOUSAND TICKETS SOLD.” Cincinnati Enquirer (1872-1922); Feb 8, 1912; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Cincinnati Enquirer pg. 14

International Bookbinder, The. United States, J.L. Feeney, 1920.

“LABOR: ORGANIZATIONS HOLD MAY-DAY EXERCISES AT WORKMAN’S HALL” Cincinnati Enquirer (1872-1922); May 5, 1895; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Cincinnati Enquirer pg. 8

"PLAIN TALK: BY GENERAL SECRETARY MCGUIRE AT THE MASS MEETING HELD BY THE UNION CARPENTERS". Cincinnati Enquirer (1872-1922); May 7, 1894; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Cincinnati Enquirer pg. 8

"Platform of the Populists." Social Policy: Essential Primary Sources. Encyclopedia.com. 25 Mar. 2021 www.encyclopedia.com.

“REPUBLICAN EXECUTIVES.: THEY MEET AT WORKMAN’S HALL” Cincinnati Enquirer (1872-1922); Mar 22, 1891; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Cincinnati Enquirer pg. 4

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Cincinnati, Hamilton, Ohio. Sanborn Map Company, Vol. 2, 1904. Map. Retrieved from the Cincinnati & Hamilton County Public Library. Genealogy & Local History Department.

Steinert, Anne. Labor History Walking Tour — Over the Rhine Museum. Cincinnati, OH. 04 November, 2019.

“THE SHOEMAKERS.: THEY MEET AT WORMAN’S HALL TO DISCUSS LOCKOUT. Cincinnati Enquirer (1872-1922); Feb 3, 1888; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Cincinnati Enquirer pg. 8

questions? comments? concerns? email me here.